Is Velocity Still King?

During the latter half of the 20th century, and likely even earlier, the phrase “velocity is king” was common among big game hunters.

Why would they say that, and is it still true today?

Well, what does velocity give you?

- Flatter trajectory.

- Increases the bullet’s ability to combat wind deflection: higher velocity = shorter time of flight.

- Energy is better retained at farther distances (all else being equal), extending the projectile’s terminal performance to longer ranges.

- Increased recoil.

I would venture to say that most people using the phrase “velocity is king” were only thinking about trajectory. Recoil might’ve have been on their mind as well, because they were going to feel it when they pressed the trigger. But I can tell you that most hunters were not thinking of increased ballistic coefficient and terminal ballistics at long range.

I can say this confidently because most hunters, even today, don’t harvest big game at distances where external and terminal ballistics come into play. By and large, true “long range” hunters are few and far between, though growing in number each year.

So, why did people want a flatter trajectory, and why would they suffer greater recoil to achieve it?

Simple: compact rangefinders didn’t exist in the civilian market until the late 1990s! As a result, hunters guessed their distance from the target, and most didn’t take shots that included holding the crosshairs above the body of the animal. It was also common for hunters to zero their rifles at 200 to give them even more reach while keeping the reticle on, not above, the animal.

When the trajectory curve is flatter, the hunter’s range estimation includes more room for error. If the bullet’s trajectory is more arched, the hunter has to be more accurate in judging the distance to the target. Higher velocities provide a similar advantage when shooting in the wind. The bullet deflects less at higher speeds (with the same projectile), meaning that there’s more margin for error in a wind call.

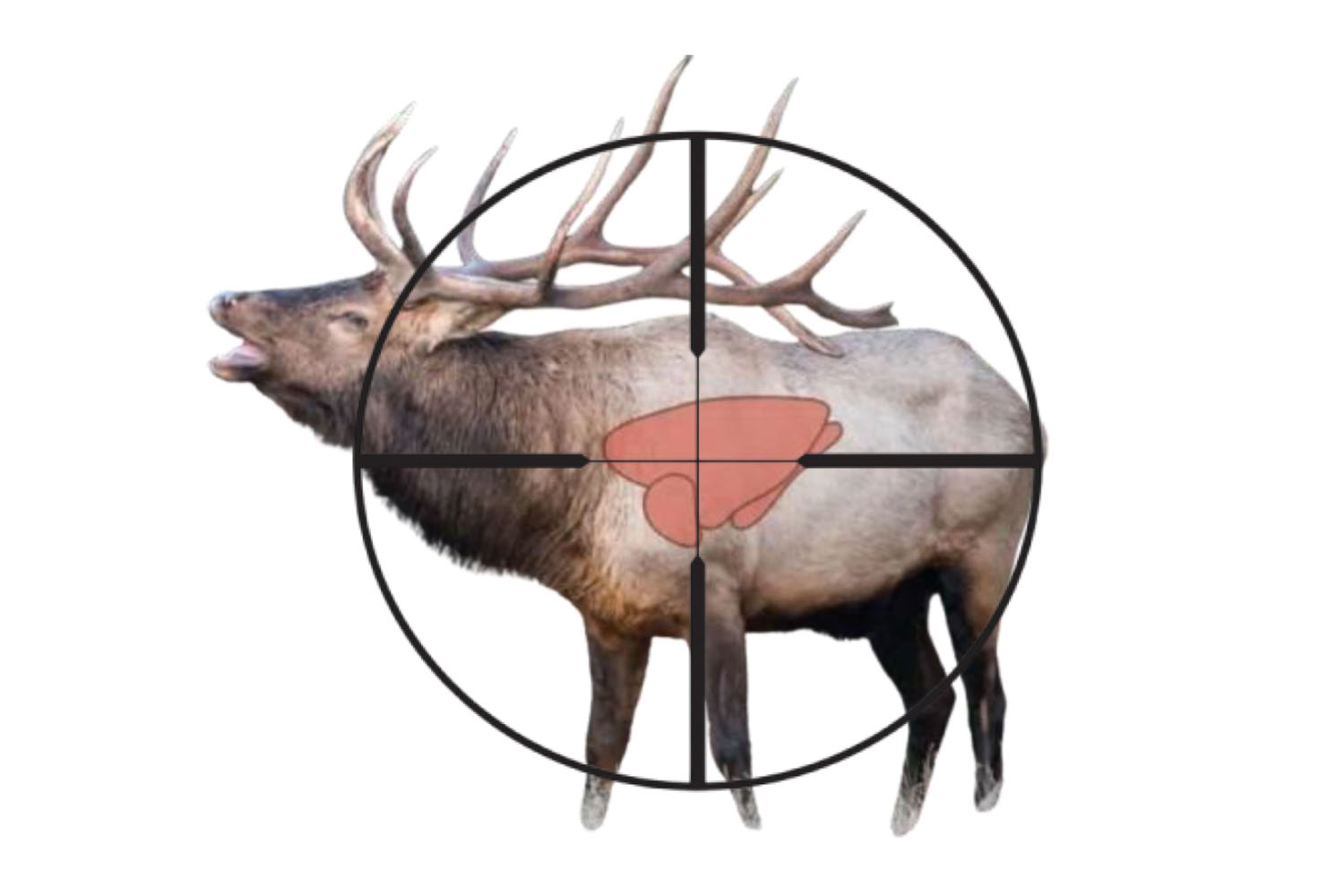

Here are a few examples that should help you visualize, using two common elk hunting cartridges from the 1990s.

The first example is based on a 7mm Remington Magnum:

- Zeroed at 200

- Muzzle velocity of 2,950 FPS

- 160 grain Nosler Partition

Let's say the elk’s vitals are roughly 18” from top to bottom. If the point of aim is center of the vitals, there is nine inches of possible error both above and below the point of aim while still impacting the vital zone. It also means that if you’re holding top of the vitals, you have 18” below your hold to place a round in the vitals.

With this rifle and ammunition combination, your bullet drops are as follows:

|

YARDS |

INCHES OF DROP FROM POINT OF AIM |

|

200 |

0.0 |

|

250 |

2.2 |

|

300 |

6.0 |

|

350 |

10.8 |

|

400 |

17.6 |

|

450 |

25.6 |

|

500 |

35.0 |

Based on this data, we know that if the hunter holds the crosshair at the top of the elk’s vitals (basically just under what you would perceive to be the spine), you could effectively kill that elk if he is anywhere within 400 yards. That is amazing. This is possible because the rifle/ammo combination in this example is relatively flat shooting. This also shows that you could aim center of the vitals and kill the elk out to 300 yards.

Now let's do another rifle/ammo combination that’s not as flat shooting. For this second example we’ll use a .308 Winchester:

- Zeroed at 200

- Muzzle velocity of 2,650 FPS

- 180 grain Nosler Partition

With this rifle and ammunition combination, your bullet drops are as follows:

|

YARDS |

INCHES OF DROP FROM POINT OF AIM |

|

200 |

0.0 |

|

250 |

3.25 |

|

300 |

8.4 |

|

350 |

15.4 |

|

400 |

24.4 |

|

450 |

36 |

|

500 |

50 |

The data indicates that if the hunter holds top of the elk’s vitals (basically just under what you would perceive to be the spine), you could effectively harvest the elk if he is anywhere within 350 yards. This also shows that you could aim center of the vitals and kill the elk out to 300 yards.

These two examples don’t show a dramatic difference, but the flatter shooting cartridg does offer a slight edge. You’d see a much larger difference when comparing cartridges like a 30-30 Winchester and a 28 Nosler, but there’s no need to go to extremes to appreciate the difference. In this example, the 7mm provides a 50 yard advantage, which might not sound like much, but it’s significant if you don’t have a rangefinder.

In practical terms, the added velocity gave the hunter a bit more forgiveness in range estimation, allowing for more margin of error before significant bullet drop became a factor.

Is it still true today?

My simple answer is “no.” Today we have very accurate range finders that can reach 3,000+ yards, along with modern scope technology that allows the shooter to dial a turret, moving the reticle in the scope instead of holding over a target. Additionally, many rangefinders on the market feature ballistic calculators and live atmospherics that instantaneously provide elevation and/or windage corrections.

It. Is. Math. The only guessing game left is wind. We now even have tools, like a Kestrel wind meter, that can confirm wind speed at the shooter’s location.

So the perks and pains to having higher velocity remain the same:

- Flatter trajectory.

- Increases the bullet’s ability to overcome the effects of drag and wind.

- Because of point #2, this allows the bullet to retain its velocity and extend its terminal performance to longer ranges.

- Increased recoil.

But now we know the exact range! So all this means is - the guy with the higher velocity doesn't have to dial as many clicks on his optic. That’s it. Even when factoring in wind, if you're using the same cartridge and there's a 200 FPS difference in muzzle velocity between two rifles, the actual difference in wind drift is minimal out to 600 yards and up to 10 mph: typically 3” (.5 MOA) or less.

So no, I don’t believe velocity is king. Chop that barrel down to 20” and let her fly. Terminal ballistics can be saved for another article, but most hunters are not shooting their rifles out to maximum lethal range anyway.